A few weeks ago, I discussed with you the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder by policemen, and how it sparked a wave of indignation and the defacing of statues throughout the world. A couple of weeks ago, we were privileged to welcome Reverend Jide Macaulay from House of Rainbow, and during the conversation that ensued, a participant blamed colonialism as the root of all evils in the Western world. Much of the current debate about colonialism is fuelled by anger and resentment, and there are countless proofs that BAME communities are worse off than the white middle class segments of our society. Racism, inequality, racial bias towards BAME people are very much part of the reality for many people.

The report of the spies

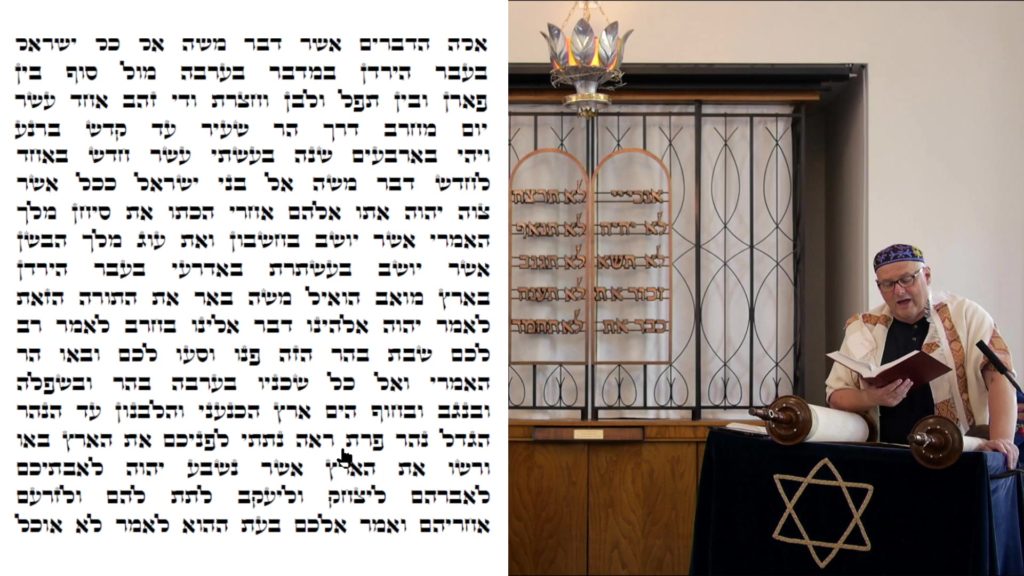

I would like today to focus on a biblical story, the report of the spies, and how it is told in a different way in the book of Numbers and its retelling in our Torah portion, the first parasha of the Book of Deuteronomy.

The Last Straw?

Prof Sarah Wolf writes:

“According to the story in Numbers, which is told from a third-person omniscient perspective, God tells Moses to send spies to scout out the Land of Canaan. The spies return after forty days and report that the Land is excellent—flowing with milk and honey—but the people who live there are powerful, both physically intimidating and well-positioned in fortified cities. One of the spies, Caleb, insists that the Land can nonetheless be conquered, but the other spies ignore him and continue to spread word of the inhabitants’ fearsomeness. The Israelites are devastated and demand to return to Egypt. Then Caleb and his fellow spy Joshua try to convince the Israelites that the Land is good and worth conquering, arguing that God will protect God’s people against its inhabitants. The Israelites, unconvinced, are about to stone Caleb and Joshua, who are saved by Moses stepping in to deliver a rebuke. Finally, God declares that this faithless generation must wander for forty years before their descendants can enter the Land”[1].

In other words, the spies were afraid, and their report rendered the Israelites despondent. We can easily understand them: they’ve been told that they were heading to a land flowing with milk and honey, the end of 40 years of wandering in the desert, and suddenly, another difficulty arises. Maybe it was the last straw that broke the camel’s back ?

Lack of faith

However, said Prof. Wolf, the book of Deuteronomy tells a different story.

“ In Moses’s first-person account, the Israelites, not God, told Moses that they want to send spies to scout out Canaan. The spies returned and said, “It is a good land that the Eternal our God is giving us” (Deut. 1:25)—no mention here of fearsome inhabitants, of internal disagreement among the spies as to how to proceed, or of Caleb and Joshua’s attempt to salvage the situation. Despite the seemingly positive report from the spies, the Israelites “sulked in their tents” (1:26) and refused to go, claiming—apparently falsely—that the spies have reported that the inhabitants are too strong. Moses reassures the people that God will protect them, and again, God announces that the Israelites must wander for forty years in the desert as a consequence of their disbelief”[2].

In this second version of the story, the Children of Israelites did not hear bad reports, and yet they went to their tents and murmured. They read between the lines, and it is this lack of faith in Moses’ promise that prompted the punishment.

Divergent stories….

Perhaps we can understand the differences between the two spy stories as exploring how a trauma can be experienced and retold in different ways according to the point of view of the speaker. Both stories provide an account of why an already traumatized generation of former slaves had to endure a secondary trauma, wandering for the rest of their lives in the desert instead of entering a land where they could settle and make a home. Yet the two accounts provide contradictory perspectives on who contributed to this trauma and in what way. In the account narrated by Moses, there is no one to blame but the Israelites themselves, and no hero besides Moses, the strong leader who alone tells the Israelites that God will protect them. Moses’s narrative even protects God from bearing any potential blame, since it is now the Israelites, not God, who requested the scouting mission in the first place. On the other hand, the third-person account in Numbers is an almost too-good-to-be-true account of Joshua’s loyalty, proving that he is the right person to be chosen as Moses’s successor.

These two divergent stories cannot definitively tell us who played what role in this disastrous event in the Israelites’ history. And remember, as we saw yesterday evening, the Mishnah tells us that these events are among the catastrophes that will be remembered on Tuesday, on Tisha B’Av. Yet these narratives can teach us an important lesson about how even our most trusted leaders might be influenced by what they want to remember, or what they want their followers to remember, in their narration of disturbing and significant events. Moses has chosen a version of the story that lets him come across as a hero.

Can we be objective about our past?

In addition to that, we can also reflect on how we retell our own past, privately or collectively. Which events do we want to emphasize? Which ones do we want to keep quiet about ? That begs a larger question: can we really be objective about our past? We all know that we tend to rewrite our own history to make us look better, or because we are ashamed of what we’ve done, or it is sometime too painful to watch back. The same applies to a society, a country, or a nation.

There is the official history, the one that is taught at school, that is invoked in public discourse, the one that makes us feel good about ourselves. Even acts of public repentance about our past is a form of self-justification.

And there is the history as told by minorities, by those who are voiceless, who can only express their views in outburst of rage and violence. That is the story told by Black Lives Matter, a story of oppression and prejudice, a story in which Black people lose, their own history in Africa written off by colonialists. Very often, African history is told only from the time Europeanscame.

How do we reconcile both versions?

So, what do we do with that ? On one hand, an official history that validates nations and elites, on the other, a history of oppression and prejudice. How do we reconcile both versions?

A first lesson can be drawn from our Torah portion.

Both versions are recorded and preserved. None is written off. Reality is always much more complex than a binary reading would suggest. One single event can be read in multiple ways, so the first task is to preserve the variety of readings and interpretations.

A second lesson is more of common sense than anything else: it is about honesty and respect. The Mussar tradition, that we are slowly bringing to KLS, teaches us that the only way to grow is to practice Cheshbon ha-Nefesh, an accounting of the soul. We have to be honest with ourselves, acknowledge our strengths and also our weaknesses. We may not always like what we see, but it precisely when something is disturbing, painful, that we know there is something that needs to be addressed.

I am responsible for my life…

I cannot engage in conversation with someone who believes at start he or she is right, and I am necessarily wrong. That is one of the reason I don’t engage with social media most of the time. An accounting of the soul requires the ability to sit in someone’s shoes, to see the world, or at least to try to see the world from their perspective, and decide where we can meet.

I am not responsible for how the previous generations have behaved, how they conducted their lives. I am, however, responsible for my life, for building honest and true relationships, for speaking out when our values are threatened.

The past stays in the past. The present is in our hands, and our future depends on how we handle it.

[1] http://www.jtsa.edu/retelling-the-past

[2] Idem