Guest post from KLS member Christine Lior Locher

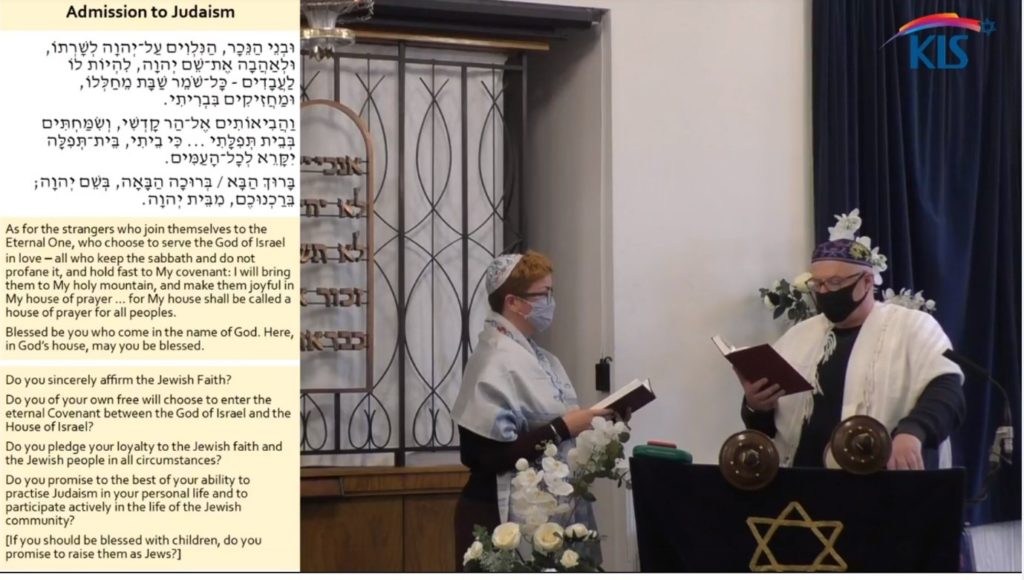

It’s official. I’m Jewish. Last Shabbat I had my admission ceremony and the paperwork. Parasha Lech Lecha: Go forth. Lockdown 2 was announced a few hours later. We managed to do the admission ceremony in the near-empty sanctuary. The community was mostly on live stream and I missed having them near, seeing all their beautiful faces, being able to hug them. The live-stream back channel is a sad replacement.

2020 was a particularly “interesting” year to complete the process, so here are some of my reflections.

Religion – like falling in love

Religion isn’t rational. There is no cost-benefit analysis or rational argument one could draw up to convince oneself or others how that is a good idea. It is a bit like falling in love, but with a way of life, a community, a tradition, a way of making sense of modern life, a way of relating to something bigger, something eternal. The idea of Israel=wrestling with God resonates deeply.

Like love, faith defies making a rational case for it, and yet it feels real, those moments when believing inches closer to knowing. Like love, faith gets sparked and fuelled by the little things, to then feel like a big thing. Like love, faith is exulting and also has moments of petty annoyance, of hitting a little too close to home, of not wanting to be with it and not being able to live without it. It is uncomfortable to write about it, how vulnerable this is, and how vulnerable we are in it. It changes the way you think about yourself, the way you relate to others, how you think about the world and what you think your role in it might be. It did for me, anyway.

As part of the conversion process you get reminded of the dangers of being Jewish. This is not just a formality, it has been a part of the process for centuries, and it is heart-breaking how true this still is. As I was writing the first draft of this text, I fell down a twitter rabbit hole of live coverage from the attacks in Vienna as they were unfolding. Next to my right elbow on my desk is the certificate of conversion in Hebrew and English, with originals stored in multiple places. It’s official. It’s also rather obvious if you follow me on twitter. It is real, and, as it changes who I am, it will change how people will respond. The responses have been mostly positive, but there is no guarantee for that.

Ruth – their people were her people

The first documented convert is Ruth, who lost her Jewish husband and then wanted to stay with his tribe, with her mother-in-law, and converted for that. She had already been living as a part of the community and was immersed in the rituals, rules and knew who she was joining. And vice versa, their people were already her people in many ways. The conversion formalized that, but the bible covers the conclusion more than the internal process that got her there. Every convert has their own story.

Starting the process, it often feels slow, though there is unarguably a lot to learn. As I was converting, I found the research on how people make change useful. I support change processes in people for a living, so this was also an interesting reflection to experience myself in this over time. I particularly recommend Herminia Ibarra’s work if you want a more academic lens on identity and change, how we (re)craft our identities. Who we (think we) are and what we do is deeply emmeshed.

You can’t think yourself into a new identity

Research recommends to shift the doing, to then get to the being. We often sit and (over)think, but you can’t think yourself into a new identity. You have to do new things, or do things in a new way. You have to live your new self out loud, step by step, and sometimes before things have fully sunk in, in all its wobbliness, as things reshape. You are road-testing your new self, finetuning, refining. And everyone sees it. That’s why a supportive community like KLS is so key. And for a while there are different possible versions of you battling out which one will move forward. All of this takes time.

I am a part of a longitudinal study of spirituality at a university in Germany, and I have in-depth qualitative interviews lasting several hours every couple of years. It is a valuable, structured practice in bigger picture self-reflection that few people allow themselves. The last interview in February 2019 reminded me how great the more Jewishly connected phases of my life were and how much I enjoyed it. I had my first connections with Judaism through a Jewish classmate in 2001 while studying in Japan and later visited her in Israel in 2005 where she had moved. I made a first start to convert in the US in 2014/15 which got interrupted when my visa ran out and I had to leave the country. So this had been bubbling for quite a while now.

Finding KLS

That reflection in the interview prompted me to reengage when I found KLS on twitter a few days later. I liked the look and feel and then met Rabbi Rene for an initial conversation. Starting with Pesach 2019, I joined services and the introduction class. Initially the services were live in the sanctuary of course, and I got to know and love the community and that now continues virtually (I miss the food though…).

Modern psychology now seems to go towards accepting that there is not one true self that needs to be found and then lived, but that things keep shifting in adulthood and that there are always multiple selves we build, test and evolve, some more plausible than others. And as we reflect, we refine the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves.

My stories are a lot more Jewish now.

Better questions

Converting is not something you do alone, you do that, out loud, with others. Community is a key aspect of being Jewish, you don’t join an abstract set of principles, you join a community of real humans. I don’t think that was as fully clear to me during round one in Boston a few years back. It goes both ways. A very obviously Christian name (Christine Maria) and German citizenship do little to make this a less awkward starting conversation. I understand that people will watch and observe for a bit who this new person is that wants to join them. It is OK to look around and find a community that fits, this has to work for both sides. For me, KLS and Liberal Judaism is a wonderful place to land in.

Many people turn to religion because they want answers. If you become a liberal Jew, instead of answers, you get more questions, but they are better questions. It still helps. I like the challenge and invitation to shape this and to make it my own, and to reshape and revisit, and to do this with others on a similar path and formidable discussions. I want my Jewish practice and my engagement with it to be alive and that helps me with it. Life has become broader and deeper and I like that a lot.

Faith can be a revolutionary act

Faith can be a revolutionary act, a clear signal that I am not an entirely rational cog operating in a late-stage capitalist high-tech machine. My ultimate accountability lies elsewhere, and I have deeper values guiding my thinking and my decision-making. It does me a world of good, that perspective and I am aware how countercultural this is.

2020 is a strange place. I never thought I’d have to colour-coordinate a face mask with my Tallit for the admission ceremony, but on the upside, it got me to wear nice, proper shoes for the first time since March.

Equal in the face of God

According to the scripture, humans are made in the image of God. And yet, in most major religions and in the more orthodox branches of Judaism, as a member of the LGBT community, I’d still be a transgressor in both who I am, and who I might fall in love with. This question matters. Identity has more than one aspect and my nonbinary bi side is going to have to live together with my religious, Jewish side and vice versa.

Liberal Judaism is one of the few places as religions go that has full LGBT equality, and it does so loudly and proudly. In front of God, I stand as an equal (with a complex identity, like every human). My Hebrew name is Lior Beit Avraham ve Sarah. Lior (“my light”, the name is gender-neutral) from the House of Abraham and Sarah, the first Jewish parents. Traditionally, one would be bat (daughter) or ben (son). Beit (from the house of) is a way to make this less gender-binary. Being able to have this conversation with the senior Rabbis as part of the process, and to experience their absolute support in finding a way to make this work in a way that reflects me was a great experience. You feel the sincerity of wanting to hold a space for everyone, and it works. My Beit Din was via Zoom, and they made it meaningful.

Phenomenal creativity!

As a lot of “life things” have moved virtually, so have the services and the learning. Thankfully, both Liberal Judaism and KLS are pretty switched on, and are phenomenally creative in how to make this a connecting, uplifting experience. I miss meeting up live and the atmosphere of the live service and the garden, but I also enjoy the creativity, the ways everyone is invited to contribute and share and how a virtual delivery makes different connections and ways to contribute possible. I join more often now that I can join from anywhere, and I spend quality time with the Sefaria app.

Next year might not be in Jerusalem but I do hope the next Passover seder won’t be streaming at my desk:

A beginning

At some point over the last 18 months, I became Jewish inside. I wasn’t when I started the process in the US even though I made what felt like big steps at the time, and I wasn’t when I (re)started the process here 18 months ago. And yet, somehow, now, I am. I felt it when I declined to work on Yom Kippur and when the Cello at Kol Nidre sunk so deep and felt so good in all the pain. It felt heavy. Good, and heavy. I felt it when visiting Israel, where it felt warm and confusing, at times so light it almost hurt.

And now in a drizzly England it is starting to feel normal, different on different days as it is always there, in some way or another as one of the parts that form me, like that is just who I am now, and that includes being Jewish. It has now become a home. Some assembly required, still, but a home of sorts. A home in a deep culture and a community, with strands that are European, American, Middle Eastern, African and also global. For someone who lived in 6 countries on 4 continents and first learned about Judaism in Japan from an American who wore modest dress to the Techno clubs, this all somehow makes sense.

This is not a conclusion. If anything, this feels like a very wordy starting paragraph. The rest of the story is still being written.